The fight for user-centric AI starts now

Why we need AI agents that serve us, not platforms

For those interested in developing AI tools that are truly user-focused and ethical, check out The Ethical AI Designer. Also, feel free to reach out if you'd like to collaborate—I'm always open to discussing new opportunities.

Last week I had some fun imagining what might happen if AI agents were introduced into the workplace. Some of it was based on research around agent miscoordination and collusion - where cooporation between AI agents becomes undesirable. I won’t give the ending away - you will need to read it here! In the story, Leah, an employee tired of feeling disempowered, decides to create an AI agent to act as her personal representative. It’s an agent that advocates for her interests, offering some pushback against the Teams Bot that’s always breathing down her neck.

What if in the future this became the default? Agents that don’t act in the big platform’s interest but in our interests instead? This is exactly what the brilliant paper ‘Resist Platform-Controlled AI Agents and Champion User-Centric Agent Advocates’ argues for. It’s a vision of a future where AI tools aren’t reinforcing the power of big platforms but are instead designed to help us avoid lock-in and regain some control.

The problem of lock-in

You might be wondering what I mean by lock-in. Think of WhatsApp and now imagine you are sick of it and want to try using another messaging platform. How easy would it be to switch to it? I can tell you from personal experience, not easy at all. With all of your contacts already on WhatsApp, not to mention its convenience, it’s a really hard sell. Even if you leave, you would have to convince all your contacts to move with you, and then they would have to convince all their contacts to move too and so on. That’s being locked-in. When I try to bring this up with people, it’s just become so normalised that the fact this big tech giant has so much power over us doesn’t even faze people.

With AI agents, it won’t just be an app that will lock you in but an entire ecosystem of platform-controlled agents, guiding your every choice. The authors of the paper call these “Platform Agents,” defined as:

Go-betweens controlled by incumbent or aspiring platform companies, designed to act in the platform companies’ interests.

They warn:

We should expect platform agents to amplify the power already concentrated in major platform companies, by (a) enabling platform companies to engage in heightened surveillance; (b) more completely controlling the allocation of users’ attention; (c) extracting additional rent from transactions they intermediate; and (d) more assertively policing users’ behavior.

When AI goes wrong in hiring

These risks aren't hypothetical. We're already seeing real-world examples where AI systems—designed and deployed by powerful platform companies—are being accused of making high-stakes decisions that disadvantage individuals. One example currently making headlines is the lawsuit against Workday, whose hiring tools are used by over 11,000 organisations around the world. As CNN reports, the people suing Workday, all over the age of 40, claim they submitted hundreds of job applications through its system and were rejected each time—sometimes within minutes or even seconds of applying. Workday claims that it does not screen prospective employees for customers and that its technology does not make hiring decisions.

But one applicant has a different take:

Mobley claims that he was rejected time and again — often without being offered an interview — despite having graduated cum laude from Morehouse College and his nearly decade of experience in financial, IT and customer service jobs. In one instance, he submitted a job application at 12:55 a.m. and received a rejection notice less than an hour later at 1:50 a.m., according to court documents.

As does this one:

Jill Hughes, said she similarly received automated rejections for hundreds of roles “often received within a few hours of applying or at odd times outside of business hours … indicating a human did not review the applications,” court documents state. In some cases, she claims those rejection emails erroneously stated that she did not meet the minimum requirements for the role.

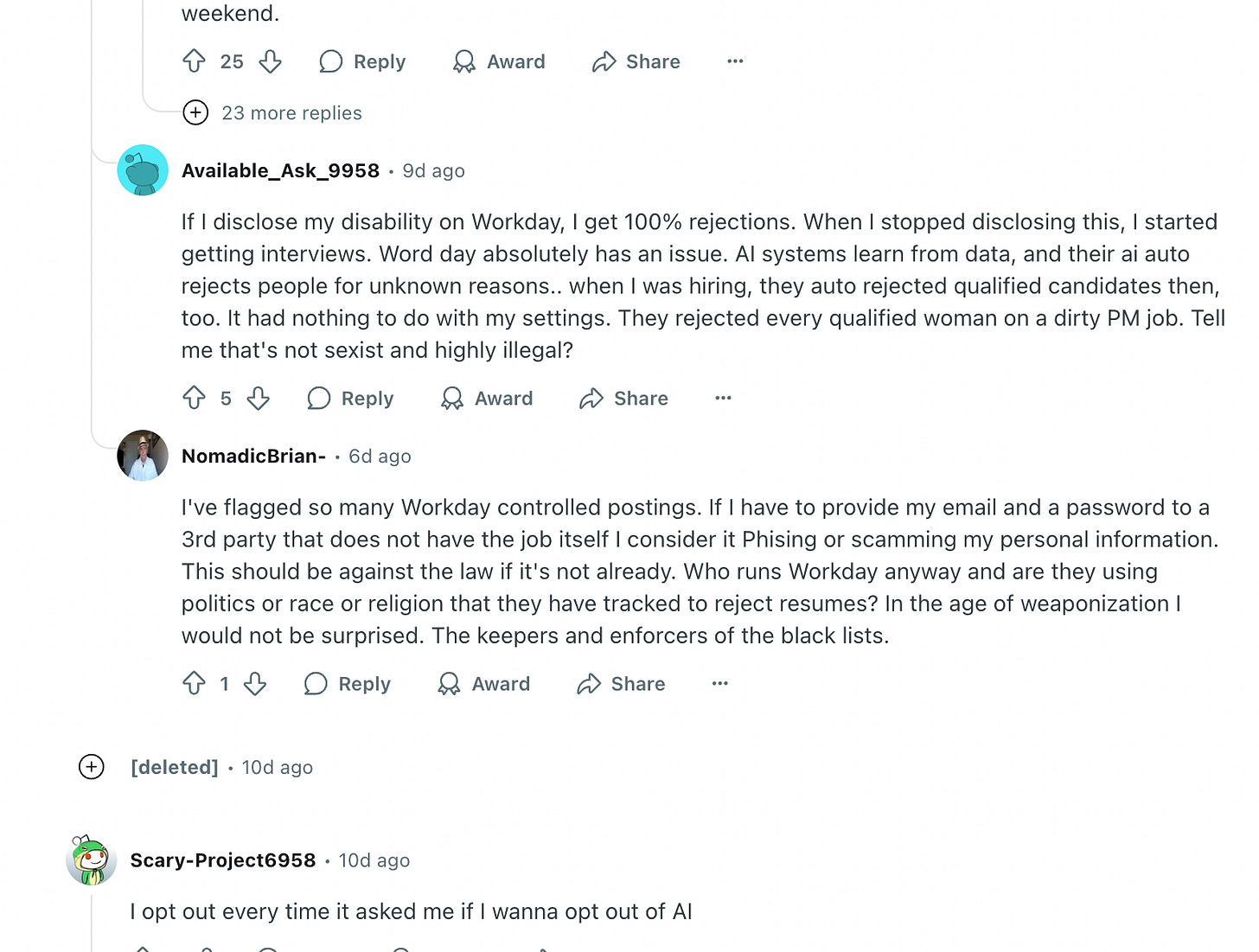

And according to some Reddit users, they are experiencing the same thing:

When biased systems get agents: what could go wrong?

Despite clearly facing some challenges with its current hiring system, Workday has since announced its Agent System of Record (ASOR), alongside a new AI Agent Partner Network. These include a "Recruiting Agent" and a "Talent Mobility Agent," designed to help organisations hire, onboard, and manage AI agents just like they would human workers.

This brings us to a crucial turning point. If automated rejection systems already show signs of baked-in bias—as the Workday case suggests—then layering AI agents on top could quietly make things worse. The lawsuit already highlights rejections occurring "within minutes or hours" or "at odd times outside of business hours," indicating deep automated processing of applicant data. If the underlying data or algorithms used for training these new agents are implicitly biased, this enhanced surveillance could amplify existing discriminatory patterns.

In a nutshell, we could be looking at:

bias at scale: agents trained on historical data could inherit—and magnify—biases around age, gender, or background, quietly shaping who gets hired, promoted, or even retained

opaque systems: rejections or recommendations might come from agents with no explanation or human touch - leaving users baffled and confused

blurred responsibility: with agents “acting” on behalf of organisations, the question of who’s accountable for their decisions becomes murky—and easy to deflect

increased corporate control: Workday’s system allows businesses to set specific parameters for how AI agents operate within the workplace. This includes controlling the data agents access and tracking their outcomes, providing businesses with deeper control over both human and digital workers

potential for increased surveillance: the extensive data Workday draws from (like HR and financial records) creates the potential for monitoring not only the performance of employees but also their behaviour and interactions within the company. This level of oversight can have both positive and negative impacts, especially when it comes to employee autonomy and privacy

data sensitivity: as AI agents handle tasks such as payroll, recruiting, and talent mobility, they gain access to highly personal information about employees. This makes it crucial for businesses to carefully consider how they use and protect that data

What if AI agents worked for you?

But as the researchers in the paper argue, “User-centric agent advocates could level the playing field”. They say that although the current trajectory shows a move towards platform agents, this doesn’t have to be an inevitability. They put forward some suggestions about how AI agent advocates might work in practice.

These agents would:

run locally or on trusted infrastructure, not embedded deep in platform ecosystems

shield you from excessive surveillance or manipulation

help you make choices based on your values—not the platform’s

push back against lock-in, and help you move freely between systems

Why should we care?

At this point, you might be wondering: why does this matter for me? Because just as we’ve seen in hiring, these decisions shape public outcomes. If companies are not being transparent that an AI was behind the reason for you not getting hired, this matters.

The way businesses deploy AI today will shape how workers are treated in the future. If platforms are allowed to use agents to track and manage employee performance at a granular level, this could lead to new forms of surveillance that extend beyond just the workplace. Your personal data, your work habits, and even your interactions could be monitored in ways that limit your personal autonomy and control. We also need to think about how AI agents are deployed from the start. It’s not just about protecting individuals from surveillance—it’s about setting the rules for how companies and developers design these tools in a way that respects users' rights.

But as the authors argue, for any of this to happen, developers and AI researchers—and society more broadly—need to undergo a mindset shift. We have to stop seeing platform agents as inevitable and start recognising that how we design and deploy them is a choice.

This isn’t just a design problem; it’s a systemic one. Public access to compute, open interoperability protocols, strong safety standards, and meaningful market regulations will all be essential if we want to build AI agents that truly work in users’ interests—not platforms.